An Australian Story

The beginning of a movement for social change in Australia

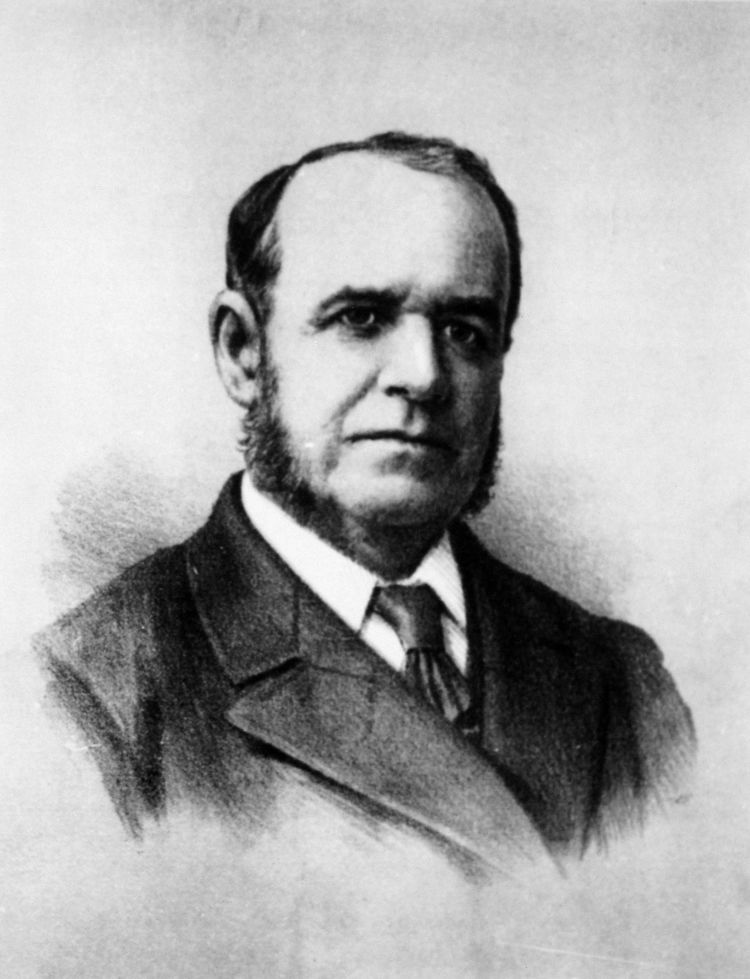

On 27 November 1900, Sir Arthur Renwick rose to his feet in the Legislative Council to speak on behalf of a law that would introduce an old-age pension in New South Wales. It would be the first in Australia.

The pensioners would have to be over 65, have lived in New South Wales for 25 years, have an income of not more than £52 per year, and be of good moral character — no criminals and nobody who had deserted a wife or a child could apply. Single pensioners would receive 10 shillings, and married couples 15 shillings per week. The scheme had been costed at £400,000 per annum.

'Why should we not pay for the aged poor?' Renwick asked. 'Poverty is no crime... old-age itself works against the power of any man to maintain himself and to obtain a means of living.' And it was ‘utterly fallacious,’ he said, to argue that the prospect of a pension would discourage young people from saving for their old-age.

Playing upon the competitive spirit of his colleagues, he insisted that New South Wales should lead the way. As the premier state, it should set an example to the rest of the country.

Despite dire predictions that the costs would bankrupt the state, that it would reward the wasteful and inefficient, and that it would attract poor old people from all over the country – arguments that are still made today about any form of social welfare – the law was passed.

In 1900 Sir Arthur Renwick was at the height of his powers. A member of parliament for 21 years, Vice-Chancellor of Sydney University, president of Sydney Hospital and the NSW Medical Board, and president of The Benevolent Society for two decades, he was also a successful businessman and a noted philanthropist. He moved in the highest social and political circles.

The culmination of a five-year advocacy campaign, the Old-Age Pension Act was a personal triumph for Arthur Renwick, but it was not a new idea. The Benevolent Society, Australia’s oldest charity, had begun urging the government to introduce an old-age pension in the 1860s, and despite dire warnings this would create a class of paupers, other charities began adding their voice to the chorus for change in the 1880s.

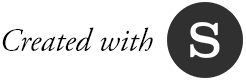

From his long association with The Benevolent Society, Renwick knew how badly this reform was needed. Although the Society had been relieved of housing indigent old men by the government in 1862, it continued to feed, clothe and assist with the rent of many more who refused to go into an institution. The cost of this 'outdoor relief' was becoming prohibitive. It was time for the government to act.

Misery Hardens the Heart

In 1895 Arthur Renwick forced the government's hand by establishing The Old-Age Pension League. It ran a highly professional, successful publicity campaign: holding public meetings to raise public awareness about the plight of the old and destitute, enlisting the help of influential supporters, briefing the press, lobbying politicians and finally steering the bill through parliament.

Few of Renwick's parliamentary colleagues would have known more than he about the underside of their privileged world. On his return from medical school in Edinburgh at the age of 25, he had been thrown into the deep end as a visiting medical officer for The Benevolent Society. It was unpaid work, carried out while he built a private medical practice.

Because there was no social security system in Australia in the nineteenth century, voluntary organisations or charities like The Benevolent Society cared for the sick, the poor, deserted wives, abandoned and orphan children, unmarried mothers, and those who were too old to work. They were funded by donations and sometimes by government grants.

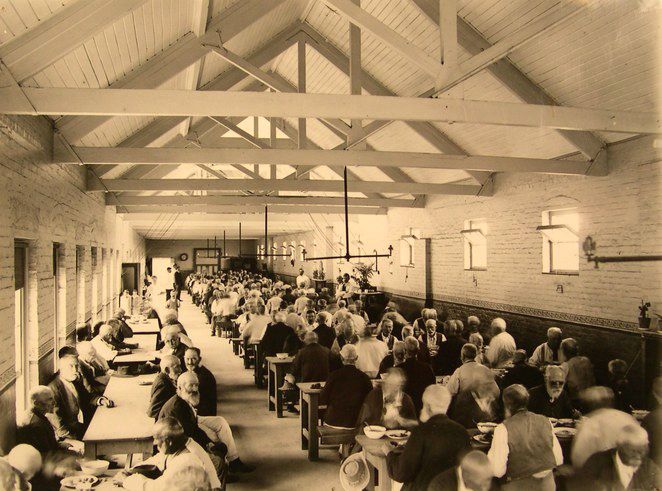

The Benevolent Society Asylum in George Street in Sydney where Arthur Renwick went to work in 1862 retained its maternity wards and continued looking after destitute, incapacitated and sick women and children who could not be admitted to the Randwick Orphan Asylum. As medical officer, he overhauled and modernised the 'lying-in' or maternity hospital, and when promoted to secretary, streamlined the management of the Asylum and drew up plans for a new hospital. In 1879 he was made President.

It was Dr Renwick's duties as a pathologist at the Asylum that exposed him to the ravages of poverty, violence and illness. Carrying out postmortems in the morbidly named dead-house, Renwick could not ignore the marks of suffering and deprivation on the bodies he dissected. In 1869 he testified at the inquest into the death of Susannah Brady, whose body had been been found in a hollow tree in Ramsay's bush at Ashfield, only metres from comfortable, middle-class homes.

He told the coroner:

I have examined the body of the deceased, which was that of a woman about 50 years of age. The body was in a filthy neglected state... The eyes were sunken in their sockets, the muscular parts of the body wasted to an extreme degree, and the whole appearance was that of emaciation. The left leg was ulcerated from below the knee to the foot, the ulcers of a gangrenous character eating into the foot. I am of opinion that the cause of death was exhaustion of the system from the neglected ulcers of the leg, from exposure, and from starvation.

Too much exposure to misery hardens some, but unfortunates like Susannah Brady aroused compassion in Arthur Renwick. Why? What made this gifted young man who could have become a complacent society doctor use his prodigious skills and energy to do good?

The Benevolent Society Asylum in George Street 1901

Using Wealth for Philanthropy

Much credit must go to his parents, particularly his father, George. In 1841 George Renwick and his wife Christina arrived in Sydney as bounty immigrants from Glasgow in Scotland with Arthur, 4, and William, 3. George, a bricklayer and later a plasterer, was ambitious and had a sense of adventure. In 1851 he joined the exodus to the Victorian goldfields, taking 14-year-old Arthur with him. According to family lore, Arthur injured his foot so badly in the camp at Ballarat that a doctor had to be called in, and this chance meeting inspired the boy to become a doctor himself.

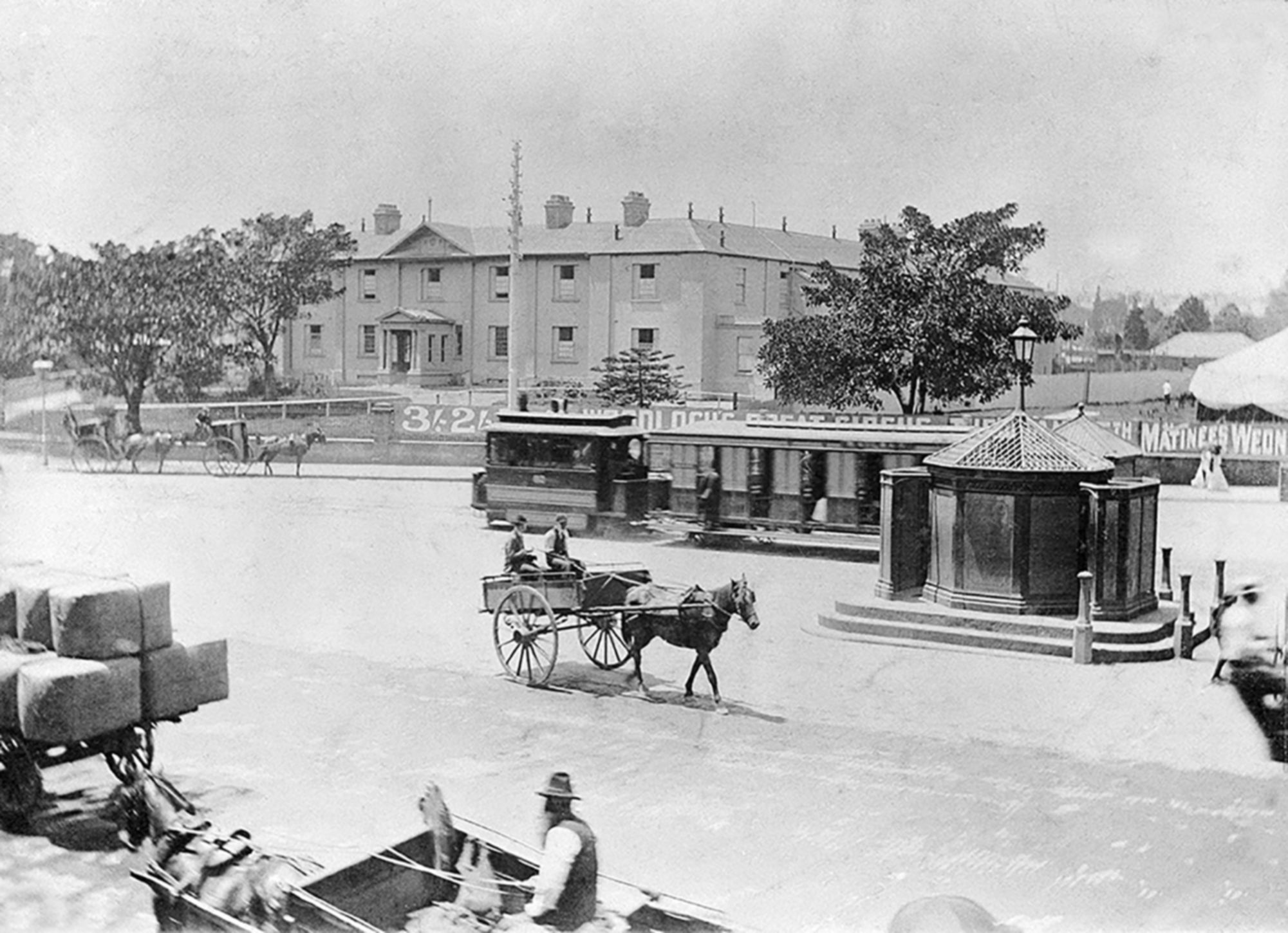

Did George Renwick find gold? We don’t know, but a lucky strike would explain how he could afford to buy a three-story terrace house in a fashionable new development in Pitt Street, Redfern, and educate Arthur first at Redfern Grammar School, and later at the new University of Sydney, where he obtained a Bachelor of Arts, followed by a medical degree at the prestigious Edinburgh University.

Arthur would not have remembered the hardships and privations of life in Glasgow's slums, but his parents would never have forgotten them. The philosopher Thomas Hobbes characterised human life before the development of society and laws as 'poor, nasty, brutish and short', but this applied equally to the lives of most people in Britain’s cities in the first half of the 19th century. Industrialisation had helped a small minority to prosper, but sickness was a constant threat in the crowded, insanitary tenement slums of Glasgow’s East End, and only the strong and the lucky reached the age of 40. Typhus broke out in Glasgow the year the Renwicks emigrated.

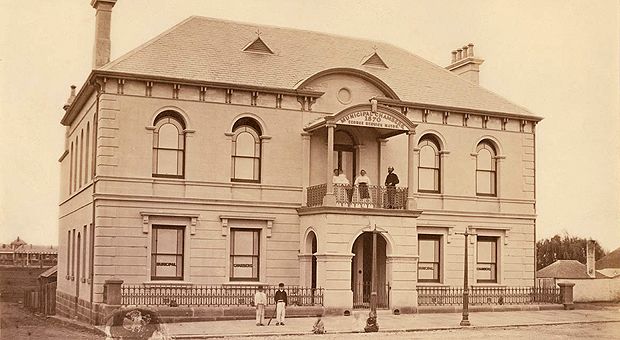

Over the next 56 years, George Renwick transformed himself from a penniless immigrant tradesman into a successful politician and a wealthy property developer. He entered local politics the year his son returned from Edinburgh and was later elected first mayor of the Municipality of Redfern. It was from their father that Arthur and his siblings learned the efficacy of hard work, ambition and networking.

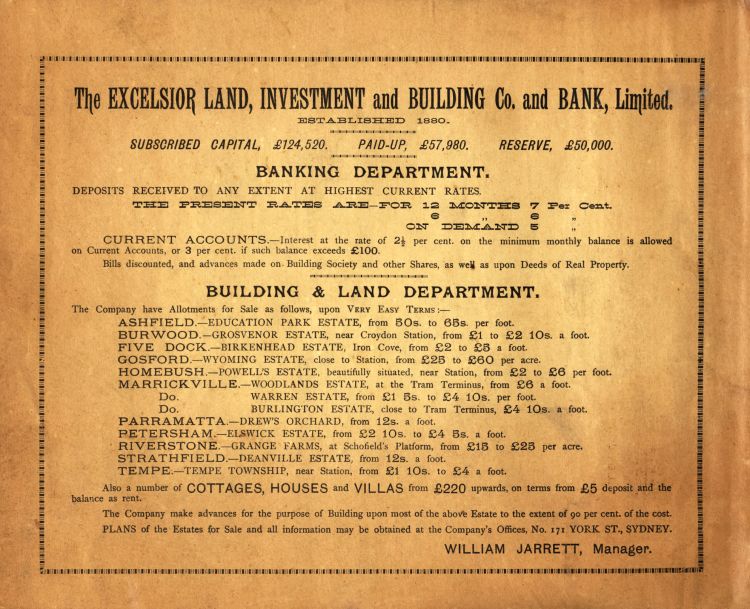

As is often the case, business went hand in hand with politics. In the 1870s George and several colleagues in the building trades set up the Industrial and Provident Permanent Building Society, a 'friendly society' that enabled the directors to assemble small savings and channel them into housing. From there it was a short step to property development. In the 1880s, at what would be the beginning of a land boom, he became a director of the Excelsior Land Investment and Building Company and Bank, which built subdivisions at Marrickville, Leichhardt and Toronto on the central coast. Not the sorts of men to hide their lights under a bushel, the developers named the streets in these estates after themselves.

The Renwick children also learned compassion from their parents. George and Christina were evangelical Christians who believed that the strong had a duty to help the weak. When George died in 1897 at 86 — 46 years longer than he could have expected to live in Glasgow — he had been been president of the Randwick Asylum for Destitute Children for 25 years, a director of the Deaf and Dumb and Blind Institution for many years, and had been on the committee of The Benevolent Society since 1875.

George Renwick had done very well for himself and his family, and he did good for others. Either because of George’s example, or because he wanted to outdo his father, Arthur Renwick followed the same path, but with the advantages of a good education, a gentle upbringing and his father’s connections, he achieved more and rose higher.

Argyle Terraces, Pitt Street Redfern, Arthur Renwick's home until his marriage

Mayor George Renwick on balcony of new Redfern Town Hall in 1871

Excelsior Company Contract Flyer

The 'Sussex Street Murder'

For four years after his return to Sydney, Arthur was relatively unknown, but in 1866 his association with The Benevolent Society, and a dazzling feat of medical deduction, made him a celebrity and gave his private medical practice an invaluable boost. In October that year parts of a woman's body were found in a rubbish heap behind the Walter Scott Inn at the Haymarket. Dubbed the 'Sussex Street murder', the ghoulish crime riveted New South Wales for months. Arthur carried out the post mortem, and not only did he come up with a description of the victim, but he also suggested who the murderer might be.

The body parts belonged to a small woman of 25 to 35 with prominent cheekbones, a slightly receding forehead and an aquiline nose, he concluded. She had been beaten to death with a heavy object such as the back of an axe, and her killer had tried to hide her identity by burning parts of the body. And, most importantly, the dissection looked like the work of a butcher. Armed with these clues, the police quickly arrested William Henry Scott, a 29-year-old butcher, and charged him with the murder of his wife, Annie.

Bessie Saunders, a Strong Woman

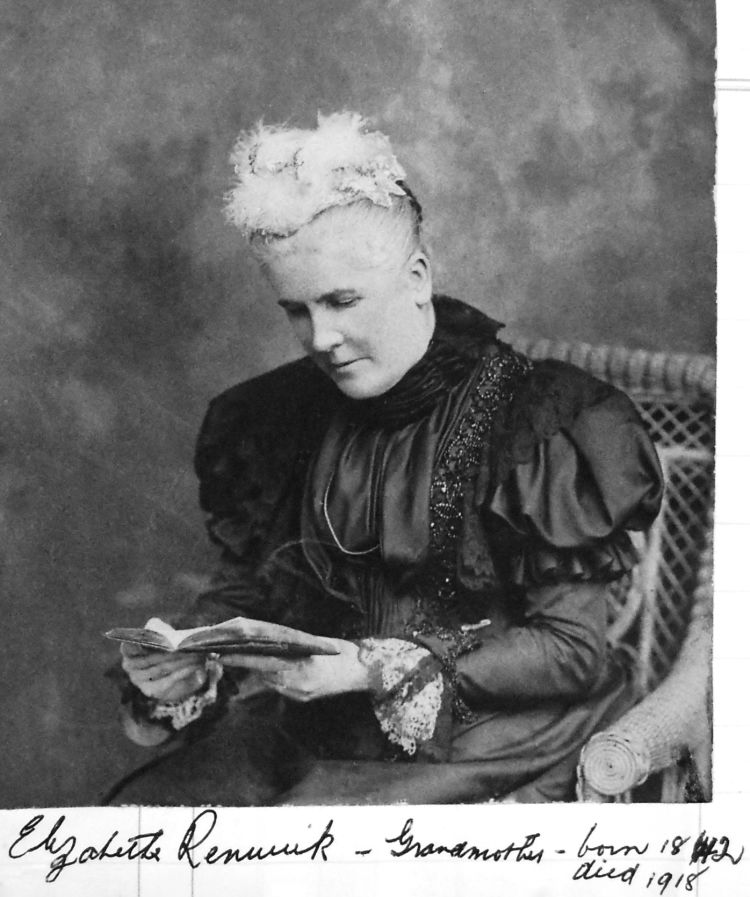

With his name in the news and his private practice flourishing, Arthur Renwick married Elizabeth 'Bessie' Saunders in the Congregational Church in Redfern in 1868. Arthur had started life as a Presbyterian and Elizabeth as a Baptist, but both their fathers had converted to Congregationalism, a nonconformist protestant denomination that became become popular in the 19th century. In a time when religious bigotry was rife, the Renwicks were notably tolerant: their eldest son, Arthur, became an Anglican minister, and their son, Charles, a doctor who served with the AIF in World War 1, was a Methodist.

Arthur Renwick did not choose a spoiled socialite as a wife. At 24, Elizabeth Saunders had led an adventurous, tumultuous and insecure life. Her father the Rev. John Saunders had come to New South Wales from England as a Baptist missionary in 1834 and took over a small, disorganised and demoralised congregation. Rough and rackety New South Wales was suffering from the social problems that accompanied a steady flow of convicts from Britain.

Through a campaign of preaching, adult baptisms, lectures and networking, John Saunders made an indelible mark on the moral landscape of the colony. Appalled by the damage caused to families by drunkenness, he became the voice of the temperance cause, but he also campaigned for the alleviation of poverty, public education, and the rights of Aborigines. Saunders health began to fail, and in 1847 the family returned to England, and when he died in 1859, aged only 53, his wife and daughter were left penniless. The Sydney Morning Herald raised £650 for his widow, and after her daughter had finished her schooling, Elizabeth Saunders brought her back to Sydney.

If Arthur Renwick was influenced by his father, he was also influenced by his father-in-law. Hard work, sacrifice and evangelical Christianity had been the air Bessie Saunders breathed from birth. In Arthur Renwick she found a life partner who shared her religious beliefs and her thirst for social justice. She would sit on the women's committees of many of his charities, and supported her own causes, which included the Womanhood Suffrage League of NSW.

But Bessie Saunders knew what it was like to face destitution. It was already clear that Arthur, unlike her impractical father, would become successful in the worldly sphere as well as the spiritual, and she and their children would never have to fear poverty and social exclusion.

Like his father, Arthur went into politics, but at the state level, where he could achieve more. He served in the Legislative Assembly from 1887 and in the Legislative Council from 1888 until his death. He also made a considerable fortune in business, becoming director of an insurance company, a building society, and the Australian Widows' Fund.

Lady Elizabeth Renwick

Sr Arthur Renwick, president of The Benevolent Society 1979-1908

Elizabeth Christina Renwick, who died at sea aged 19

Rev Arthur Renwick with wife Alice and children Arthur III, Charles and Ruth at Gosford

The Depression

Up until 1885, Arthur Renwick had led a charmed life. But over the next two years he lost his younger brother George, also a doctor, and his younger sister, Anne, both at 27, and in 1890 his unmarried sister Elizabeth died at the family home in Pitt Street aged 43.

To add to his woes, Australia slid into an economic depression in the 1890s. The property boom went bust. Home buyers defaulted and companies like George's Excelsior and Arthur's Industrial Building Society failed, and banks followed suit. Arthur, who had been Secretary of Mines in the early 1880s and had invested heavily in mining shares, lost a fortune; the irony is that the crash was caused partly by men like the Renwicks, who had created the fatal property bubble.

And then in 1893, the worst year of the depression, his eldest daughter, Elizabeth Christina 'Bessie' Renwick, who sounds jolly and headstrong, died on board ship on her way home from a trip to Scotland with her mother, the day after her nineteenth birthday. Her great-niece, Ruth, described the event in her scrapbook: 'This much awaited trip abroad ended in disaster. Bessie, always a bit of a tomboy I gather, fell heavily during gymnastics on board ship. She died and was buried in the Red Sea.'

With his busy schedule and myriad committees, Arthur Renwick would have had little time to spend with his six sons and two daughters — it was his wife who wrote to her eldest son Arthur Jr at Oxford to break the sad news about his sister — but his daughter's sudden death so far from home must have shaken him to the core. Its effect on Lady Renwick, who had to deal with the formalities alone, can only be imagined.

Campaigning for Children & Older Australians

Despite these setbacks, Arthur threw himself into work. In 1894, while chairman of the Children's Relief Board, he helped shepherd the Children's Protection Act through Parliament to outlaw baby farming — the disposal of unwanted illegitimate children by neglect and sometimes murder. Later he had the Children's Relief Act amended so that the government would pay widows and deserted women to keep their children instead of sending them to the orphanage or boarding them out to strangers. It would be another 30 years before the widows' pension and child endowment were introduced in NSW.

In 1894 Arthur Renwick was knighted for his oversight of the successful NSW court at the Chicago World's Fair, the last of several exhibitions he organised. A year later he began the campaign for the old-age pension. And after the NSW Government resumed the site of the Asylum in George Street in 1901 to build Central Station, he finally achieved another long-held ambition by building a modern obstetric hospital. The Royal Women’s Hospital at Paddington opened in 1905.

But his trials were not over. In 1903 George Gordon, the Renwicks' fourth son, died in the Coast Hospital at Little Bay at 22, probably of tuberculosis. His parents would have still been grieving the following year when financial problems forced them to leave their home, Abbotsford House, on the Parramatta River at Five Dock. It must have been a wrench. They had built the ostentatious 'Boom Style' Victorian mansion with its spired cupolas and its own chapel in 1878. It survives unaltered in private hands and is protected by a heritage listing.

The Renwicks moved to Woodstock, which was smaller but boasted its own park and a famous garden, in Church Street, Burwood. It is now owned by Burwood Council.

Sir Arthur Renwick died there of heart failure in 1908, aged 71. Every newspaper in NSW and many in other states ran laudatory obituaries. In Sydney, The Daily Telegraph called him:

A good churchman, an argent worker in charitable movements, a ripe scholar, and a born organiser.

They predicted his death would be deeply regretted. Bessie joined him in the family plot at Rookwood 10 years later.

Why then have the Renwicks been forgotten?

Together they made a remarkable contribution to the social, political and moral life of New South Wales. With Bessie providing emotional support, a stable home life and almost certainly advice, Arthur achieved social reforms that resonate still: childbearing became safer, widows were able to raise their own children, and the old and poor like Susannah Brady no longer had to resort to charity or die alone and forgotten.

Social Change

References

- Hansard, Legislative Council, 27 Nov 1900, 5747-8.

- Ron Rathbone, A Very Present Help: Caring for Australians Since 1813: The History of the Benevolent Society of New South Wales, State Library of NSW: Sydney, 1994, p. 65.

- 'Horrible death from starvation,' Empire, 1 December 1868, p. 2.

- N.G. Butlin, Investment in Australian Economic Development, 1861–1900, 1964, 2013, p. 245.

- Sydney Morning Herald, 24 June 1897, p. 9.

- 'Central Police Court. The murder case (ninth day) concluded,' Sydney Morning Herald, 1 November 1866, p. 3.

- Rod Benson,' The Inaugural John Saunders Lecture: The professional and personal witness of the Reverend John Saunders in Sydney, 1834-1847,' Tinsley Institute, Sydney, 1 May 2008, pp. 3, 17.

- 'Sir Arthur Renwick, M.D., F.R.C.S. (1837 – 1908),' Parliament of New South Wales,https://www.parliament.nsw.gov.au/members/formermembers/Pages/former-member-details.aspx?pk=718.

Photo Credits

- Sir Arthur Renwick, Member of Legislative Council. SLNSW FL1782198

- Liverpool Men's Asylum. Liverpool and District Historical Society

- The Benevolent Society Asylum in George Street 1901. National Archives of Australia C4067 HN107

- Argyle Terraces, Pitt Street, Redfern. Gosford City Library

- George Renwick at Redfern Town Hall. Attributed to Charles Pickering, SLNSW FL1230522

- Excelsior flyer. Cultural Collections, Auchmuty Library, University of Newcastle

- Lady Elizabeth Renwick. Gosford City Library

- Dr George Renwick, President of The Benevolent Society. Canada Bay Heritage Society

- Elizabeth Christina Renwick. Gosford City Library

- Rev Arthur Renwick and family. Gosford City Library

- Abbotsford House. City of Canada Bay Local Studies Collection

- Other photos, The Benevolent Society archive, SLNSW